Introduction

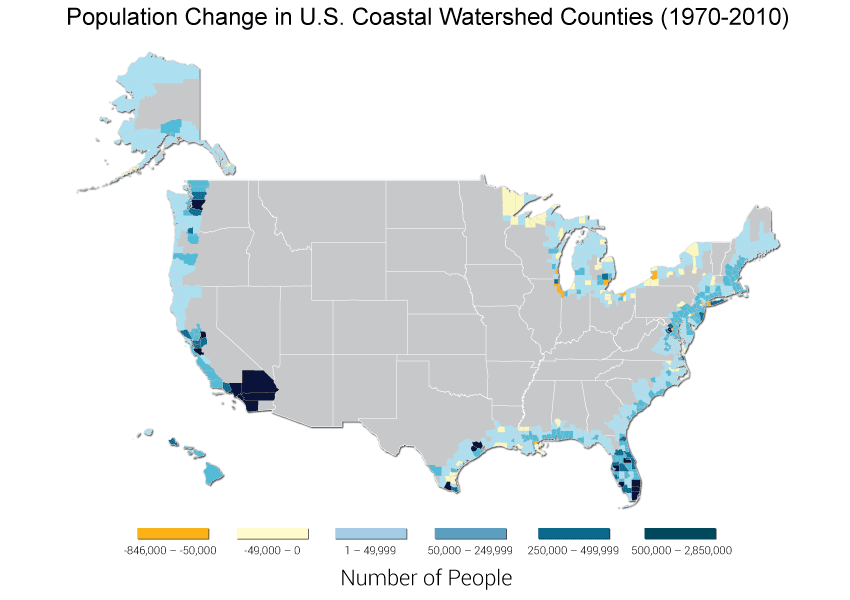

Each year, more than 1.2 million people move to the coast, collectively adding the equivalent of nearly one San Diego, or more than three Miami’s, to the Great Lakes or open-ocean coastal watershed counties and parishes of the United States. As a result, 164 million Americans – more than 50% of the population – now live in these mostly densely populated areas285,286,287,288 (Figure 25.1) and help generate 58% of the national gross domestic product (GDP).159 People come – and stay – for the diverse and growing employment opportunities in recreation and tourism, commerce, energy and mineral production, vibrant urban centers, and the irresistible beauty of our coasts.289 Residents, combined with the more than 180 million tourists that flock to the coasts each year,129,290 place heavy demands on the unique natural systems and resources that make coastal areas so attractive and productive.8

Figure 25.1: Population Change in U.S. Coastal Watershed Counties (1970-2010)

Figure 25.1: U.S. population growth in coastal watershed counties has been most significant over the past 40 years in urban centers such as Puget Sound, San Francisco Bay, southern California, Houston, South Florida and the northeast metropolitan corridor. A coastal watershed county is defined as one where either 1) at a minimum, 15% of the county’s total land area is located within a coastal watershed, or 2) a portion of or an entire county accounts for at least 15% of a coastal USGS 8-digit cataloging unit.285 Residents in these coastal areas can be considered “the U.S. population that most directly affects the coast.”285 We use this definition of “coastal” throughout the chapter unless otherwise specified. (Data from U.S. Census Bureau).

Meanwhile, public agencies and officials are charged with balancing the needs of economic vitality and public safety, while sustaining the built and natural environments in the face of risks from well-known natural hazards such as storms, flooding, and erosion.291 Although these risks play out in different ways along the United States’ more than 94,000 miles of coastline,292 all coasts share one simple fact: no other region concentrates so many people and so much economic activity on so little land, while also being so relentlessly affected by the sometimes violent interactions of land, sea, and air.

Humans have heavily altered the coastal environment through development, changes in land use, and overexploitation of resources. Now, the changing climate is imposing additional stresses,293 making life on the coast more challenging (Figure 25.2). The consequences will ripple through the entire nation, which depends on the productivity and vitality of coastal regions.

Coastal Resilience Defined

Resilience means different things to different disciplines and fields of practice. In this chapter, resilience generally refers to an ecological, human, or physical system’s ability to persist in the face of disturbance or change and continue to perform certain functions.294,295 Natural or physical systems do so through absorbing shocks, reorganizing after disturbance, and adapting;296 social systems can also consciously learn.297

Events like Superstorm Sandy in 2012 have illustrated that public safety and human well-being become jeopardized by the disruption of crucial lifelines, such as water, energy, and evacuation routes. As climate continues to change, repeated disruption of lives, infrastructure functions, and nationally and internationally important economic activities will pose intolerable burdens on people who are already most vulnerable and aggravate existing impacts on valuable and irreplaceable natural systems. Planning long-term for these changes, while balancing different and often competing demands, are vexing challenges for decision-makers (Ch. 26: Decision Support).