Introduction

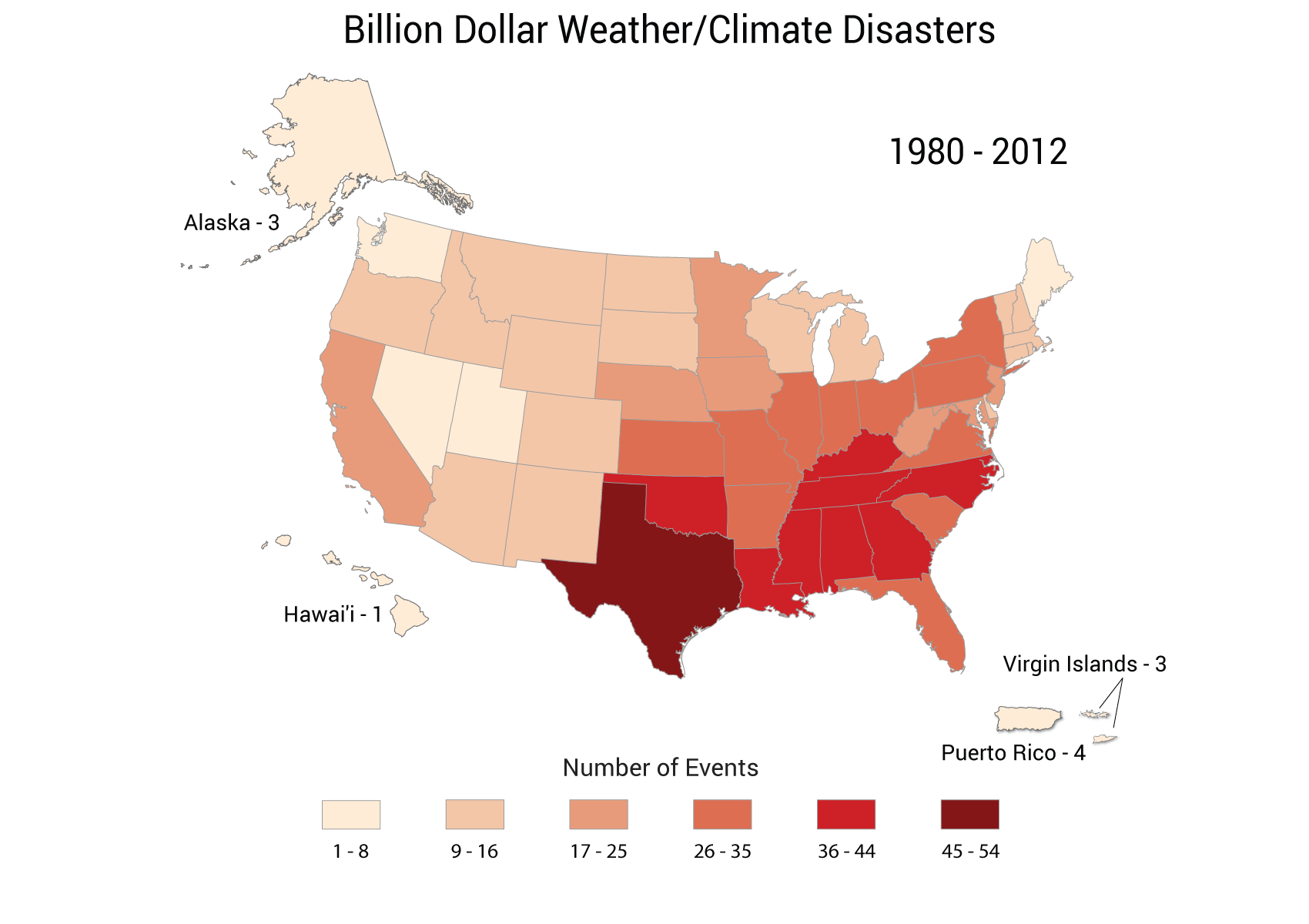

The Southeast region includes the states of Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia, as well as Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. The Highlights section below offers a high-level overview of climate change impacts on this region, including the three Key Messages and selected topics. (see Ch. 17: Southeast)